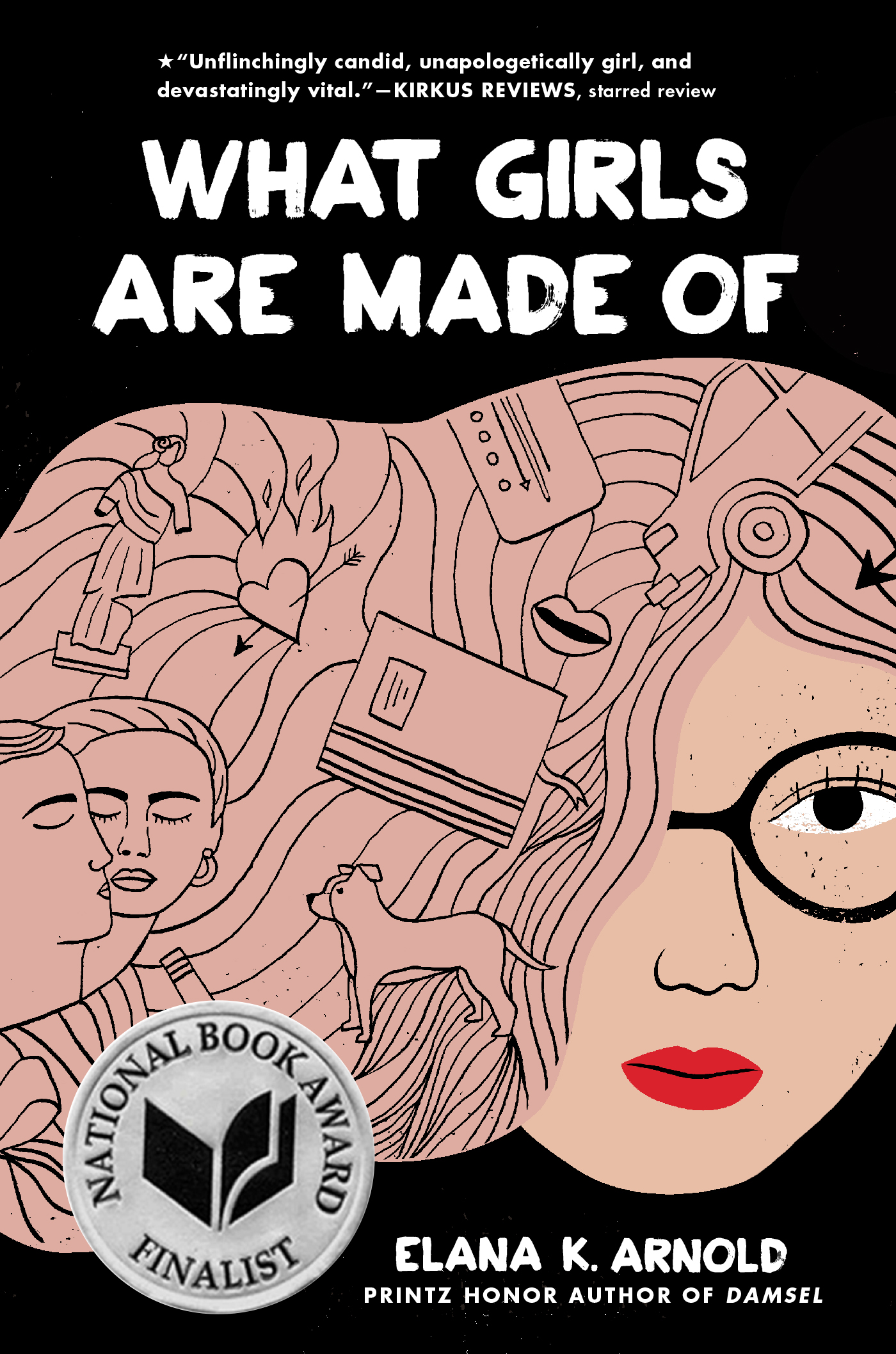

What Girls are Made Of

Publication Date: January 28, 2020 by Holiday House

Finalist for the 2017 National Book Award in Young People’s Literature

When Nina Faye was fourteen, her mother told her there was no such thing as unconditional love. Nina believed her. Now Nina is sixteen. And she’ll do anything for the boy she loves, just to prove she’s worthy of him. But when he breaks up with her, Nina is lost. What is she if not a girlfriend? What is she made of?

Broken-hearted, Nina tries to figure out what the conditions of love are. She’s been volunteering at a high-kill animal shelter where she realizes that for dogs waiting to be adopted, love comes only to those with youth, symmetry, and quietness. She also ruminates on the strange, dark time her mother took her to Italy to see statues of saints who endured unspeakable torture because of their unquestioning devotion to the divine. Is this what love is?

Buy on Bookshop Buy on Amazon Buy on B&NReviews

Pulling back the curtain on the wizard of social expectations, Arnold (Infandous, 2015, etc.) explores the real, knotted, messy, thriving heartbeat of young womanhood. When Nina Faye’s mother tells her that there is no such thing as unconditional love, that even a mother’s love for a daughter could end at any time, Nina believes her—after all, she has already seen many conditions of love at play: beauty, money, aloofness, sex. Two years later, the white, now-16-year-old not only confirms that these and more are unspoken stipulations of her relationship with her boyfriend, Seth (also white), but also finds they are part of the very fabric of cisgender girlhood that suddenly threatens to smother her. Nina’s embroiling first-person prose alternating with what are revealed to be her own short stories lifts and examines the veils that encapsulate all the “shoulds” and “supposed tos” of teenage girlhood to expose bodily function, desire, casual cruelty, sex and masturbation, miscarriage and abortion, and, eventually, self-care. Arnold interweaves myriad landscapes, from the parched affluence of California neighborhoods to the ordered sadness of a high-kill animal shelter where Nina volunteers, from the sculpted terrain of Rome’s brutalized virgin martyrs to the imperfect physicality of Nina’s own body, into a narrative wholeness that is greater than its parts. Unflinchingly candid, unapologetically girl, and devastatingly vital. ( Kirkus, Starred Review)

Nina has had a crush on Seth since fifth grade, but it wasn’t until the summer after her 16th birthday that he finally acknowledged her feelings for him. Now, Nina will do whatever is necessary to maintain his affection. She is fully aware that all love comes with conditions; her mother, in particular, has made that very clear. But as the only child of dysfunctional parents, Nina craves the attention that Seth offers. Thoughts of him occupy her every waking hour, so when she unwittingly fails his unexpected test of her loyalty, she finds herself alone and adrift, especially after she makes a startling realization. When even her best friend fails to support her, Nina looks for help and solace in unlikely places, including at a dog shelter. In an afterword, Arnold explains that this story is the result of her anger at and complicity in the rules that society applies to girls. Her overarching theme is the fallacy of believing in unconditional love. The author presents a hopeful conclusion as Nina learns that self-love and fulfillment can be found through helping others. VERDICT Because of its complex symbolism and graphic imagery, this well-written novel is best suited to mature YA readers. (School Library Journal)

Arnold’s latest reveals how capricious first love—and our trust in it—can be. Nina, 16, is trying to make sense of the obsession she feels for her first boyfriend. “I know it isn’t okay to care this much about a boy. I know it’s not feminist, or whatever, to make all my decisions based on what Seth would think,” she chastises herself. Besides, she has grown up being told by her mother that all love has limits; it can’t just surge forth unbridled. Then, just as Nina and Seth’s relationship turns more intimate, he abandons her without explanation. In Nina’s grief, she explores the origins of her longing for love, recalling a trip she took with her mother to Italy to study statues of saints, intertwining the saints’ suffering with what she views as her own. Nina’s honest musings about her vapid relationship with Seth, and also the relationship of her fickle parents, demonstrate a keen sense of introspection and self-respect. Smart, true, and devastating, this is brutally, necessarily forthcoming about the crags of teen courtship. (Booklist)