THE RED TOUR @ Mysterious Galaxy Bookstore

Anna Marie McLemore and I are kicking off The Red Tour at Mysterious Galaxy Bookstore in San Diego. For tickets and details visit: https://www.mystgalaxy.com/Arnold-McLemore-02-2020

Anna Marie McLemore and I are kicking off The Red Tour at Mysterious Galaxy Bookstore in San Diego. For tickets and details visit: https://www.mystgalaxy.com/Arnold-McLemore-02-2020

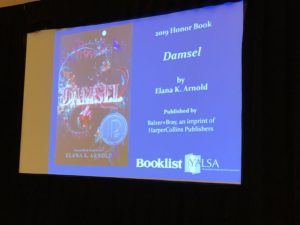

On Monday, June 24th, I attended the Printz ceremony where DAMSEL was honored alongside I, CLAUDIA by Mary McCoy, A HEART IN A BODY IN THE WORLD, by Deb Caletti, and winning book THE POET X by Elizabeth Acevedo.

Here’s what I said:

When the Printz committee called to tell me that DAMSEL had been named an honor book, I was in the audience of my daughter Davis’s performance. She was playing Jenna Roland in BE MORE CHILL, and she was amazing. It was after the curtain dropped and we were waiting for Davis that I checked my phone. I still have the message recorded. I had to sit down to return the call. My legs were shaking. And I am so very grateful, Printz committee, for your recognition of DAMSEL.

Rachel, Sam, Danielle, Karen, Teka, Jessica, Jennifer, Anna Grace, and Paula, thank you all for this incredible honor.

Being here tonight is made even more thrilling as I have the honor of sharing this space with Deb Caletti and Mary McCoy and winner Elizabeth Acevedo, all writers whose work I deeply admire and respect.

I’m indebted to MaryLynn Reise, who lent me her apartment in San Francisco, where DAMSEL was conceived, and to Martha Brockenbrough, who provided the spark.

I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have Rubin Pfeffer as my steadfast agent since 2010. I’m especially grateful that his philosophy has always been that my job is to write the books—whatever they may be—and that his job is to find homes for them. This has meant that I’ve been supported in following whatever lights me up—in this case, a sudden, fierce, and intense need to write a fantasy novel, something I’d never considered doing before.

And it has been my supreme good fortune that DAMSEL’s home is with Jordan Brown and the team of Balzer & Bray.

Jordan Brown is the kind of careful, considerate editor that every writer dreams of finding. It’s a constant joy, Jordan, to work with you on books that run the gamut from loving kindness and skunk care to dragonhearted disemboweling of the patriarchy. Thank you for your partnership. I appreciate you more than you could know.

Alessandra Balzer and Donna Bray—thank you for your willingness to elevate my exploration of embodied female rage. Patti Rosati, I so appreciate your work as Director of School and Library Marketing, helping DAMSEL find her way into the hands of adult readers who, in turn, can share her with teens. To the entire team at Balzer & Bray, thank you for helping this dragon spread her wings. And thank you also for DAMSEL’s beautiful cover.

Max, Davis, and Keith, my family who is here with me tonight—what can I say other than I love you, I love you, I love you.

DAMSEL is a novel-length original fairy tale about a world in which, in order to become king, the prince must, single-handedly conquer a dragon and rescue a Damsel, whom he will take home to be his bride. That is the way it has always been, and so the book opens with Prince Emory of Harding on his way to Do the Thing, as is his duty.

The second section of the book shifts to the Damsel’s point of view when she wakes, naked in Emory’s arms with no memory. When she asks, who am I? Where am I?, Emory basically says, don’t worry about it. You’re the Damsel, and now I’m king. Just… sit there and look pretty. And don’t ask too many questions.

DAMSEL is a book about how patriarchy hurts everyone. With some distance, I’ve discovered that DAMSEL is about other things, as well. One thing I’ve come to see is that each of my young adult books published so far ends in the same way—with a girl stepping alone, head up, into her future. DAMSEL’s protagonist Ama is different in that she flies rather than steps, but the gist is the same.

Reflecting on this, I recognized that one thing these books say is that sometimes, you can only save yourself. Sometimes, if you’ve been damaged by circumstances, family, abuse, you may not yet be in a position to lead others out of harm. Sometimes, the best you can do is to get out.

Another thing I’ve come to see about DAMSEL is that it is a book is about boundaries—who builds them, who supports them, and who tears them down. The Kingdom of Harding, where Emory brings Ama, is surrounded by a Wall which is inset with thousands of glass eyes, all blown by the Kingdom’s resident Glassblower. His is the Gaze through which we see the world.

As children, we all operate from inside borders into which we have been born. Some of the walls that divide us, we see, but others can be invisible. The teen years are when, for many of us, those walls, once translucent, become undeniably visible. And then we make choices: Do we accept them? Do we reinforce them? Or do we work to tear them down?

Some reviewers and critics feel strongly that DAMSEL is not a “YA” book. Some say its messages will go over the heads of its intended audience—presumably teen girls. Some say the content is too heavy for teen readers, that it’s too “dark,” that the book is too subversive, too angry, too disturbing, too gross.

I think these criticisms say more about the walls people want to keep around our collective damsels—teen girls—than they say about the book.

It would be a beautiful fairy tale to live in a world where no one experiences sexual assault, gaslighting, or abuse. But that is not the world we live in. Our world is one in which issues of sexual violence are among the experiences and concerns of real-world teens, and I think some of the most interesting and important work that we can do as writers of fiction is to examine real-world problems through a fantasy lens. I think teenagers deserve this—they deserve us doing the work of leaning in, of being uncomfortable, of pushing back.

I’ve come to see that part of my work as a writer of young adult fiction is to push against the walls that try to limit what “YA” fiction is. It’s deeply gratifying to be alongside Liz, Deb, and Mary, writers who have leaned their shoulder against the walls and pushed, and to be doing this work among this brilliant network of librarians, readers, authors, and artists.

They are big, heavy walls. But we are legion, and stronger. Thank you.

I’ve been told that my young adult novels are inappropriate for teens. Are they?

That depends, I guess, on what you mean by “inappropriate.” Do you mean “stuff that shouldn’t happen to young girls and women?” Then, yes. Last year’s What Girls Are Made Of examined embodied female shame and the question of unconditional love, the ways girls are asked to shrink and twist into forms others desire of them. Damsel explores rape culture, gaslighting, the male gaze, misogyny, and patriarchy in a world of damsels, dragons, princes, gowns, and glass eyes.

If, on the other hand, by “inappropriate,” you mean, “stuff that doesn’t happen to young girls and women,” then the answer, unfortunately, is no. None of the “stuff” in these novels is make-believe, and it’s precisely because the books reflect lived experience that they scare and discomfort.

Ask 15-year-old Christine Blasey if she understands the dangers of existing in a female body.

Ask Seven-Year-Old Me if she got the joke when Coach Bill said her middle splits would “come in handy in a few years.”

Ask Eighth Grade Me how it felt when her English teacher told her that she was a talented young writer and, before she could say “Thank you,” kissed her wetly on the mouth.

Ask Ninth Grade Me if she understood what her algebra teacher meant when he said, “I like the way you look in that skirt.”

Or if Eleventh Grade Me correctly inferred meaning when her journalism teacher said, upon watching her eat a cinnamon roll during zero period, “I’d like to lick yourHoney Bun.”

Ask University Freshman Me if she understood implication when a dormmate held her down, pressed his erection and razor blade against her, and said, “I could rape you, if I wanted to.” Ask her if she understood complicity as that young man’s roommate watched.

Ask almost any young woman, anywhere, and she will have a story, if you are willing to hear it.

Recently, waiting for an elevator with a group of women—some I knew, some who just happened to need to get up to the next floor—we got onto the topic of sexual assault. Between the time I pressed the button to call the elevator to the time the doors opened, each of us had shared a casual memory of an incident at the office, in a classroom, on the subway. Then, in the next breath, one of the women said to another, “Where should we get lunch today?”

It’s that casual. It’s that expected, that everyday. So common that our shared experiences didn’t even warrant a moment of, “I’m sorry that happened to you. It happened to me, too.”

I get that we don’t want to believe that terrible things might happen to our daughters. I have a daughter—I want to protect her.

I wish I could have protected her from the boy who said to a friend that he’d like her, at twelve-year old, to give him a lap dance.

I wish I could have protected her from the car full of teen boys who rolled up along her and her friends and yelled, “Hey! Do you want to fuck?”

I can’t protect my daughter by locking her in a tower, or by placing a dragon outside her door. I can’t protect all the daughters. I couldn’t even protect myself.

But I am a writer. What I cando is give words to experience. I can give them language to recognize what is happening, may happen, has already happened.

Some critics say my work is too heavy for teens. One critic recently wrote of Damsel, “The symbolism and imagery, as well as the meaning of the sexual violence that is perpetrated upon Ama, may go over the heads of less sophisticated readers…While Arnold has written a compelling flipped fairy tale and commentary on misogyny, she’s missed the mark for her intended audience.”

Actually, you will see that this criticism isn’t about my book, at all—it’s a criticism of teen female readers.

The critic seems to believe that young women won’t understand the book’s symbolism and imagery. Ah, tender critic. How I wish you were right. How I wish young girls weren’t steeped in such things in their own real, lived experiences.

Willthe symbolism and imagery, in Damsel, as well as the meaning of the sexual violence that is perpetrated upon Ama, go over the heads of its readers?

Like the rest of us, teen girls see the misogynist on the verge of being appointed for a lifetime position on the Supreme Court. They see the liar and serial groper in the White House. They hear media talking about #MeToo as a “moment” in one breath, a “movement” in the next, and they know it’s still up in the air which it will be. They hear John Kerry throwing around “like a teenage girl” as a casual insult, and they correctly hear his derision.

Teen girls don’t need us to protect them from the truths of our world. They need us to arm them. With our belief in their experiences. With our own stories, too. Women, most of you have a memory, perhaps several memories, of assault. I am sorry you carry these burdens.

Not long ago, I told my daughter about my dormmates and how they threatened to rape me. I have told her about my teachers. And I listen when she tells me the things that happen to her. I listen, and together we act.

Women, tell our girls your stories. Arm them with knowledge. And let’s stop pretending they don’t know what is happening around them and to them, every day.

It’s the least we can do.

Recently, a college student who is interested in being a writer emailed me and asked if I would answer some interview questions.

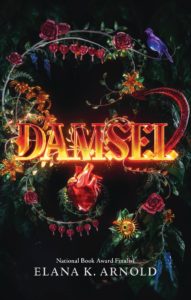

Also, I’ll share here again the beautiful cover of DAMSEL, which will be published October 2nd.

Available now for preorder!

I thought other emerging writers might find my responses to be of use, so I’m sharing them here.

Q: Where do you find inspiration for your books/writing?

A: I find inspiration all around me—in my own history; in current events, politics, and culture; in other art (books, TV, film, music); in nature; in animals and children. The job of a creative person is to be curious and pay attention.

Q: What does your writing process look like? Do you set a plot for a book/series first or see where inspiration takes you?

A: My process varies depending on what I’m currently working on and where I am in the process. I do a lot of wandering around, imagining, much the way a child loses herself in daydreams, except with the daydreams populated by potential or current characters. I rarely plot; I begin with an idea—either for a first line, or a character, or a setting. Sometimes the voice comes to me; sometimes it takes patience. Some days I work on writing new words for five hours or longer; other days I don’t write anything down at all. I wish I had a prescriptive approach I could share, but I don’t. Every time I begin a new project, I feel like I’m starting for the very first time. And that’s because it is true; each time I begin a new story, it’s the first time I’ve told that story, and I learn how to tell it by telling it.

Q: What does your editing process look like? How do your rough drafts compare to your final drafts?

A: Most of my stories grow in revision; the novel I’m currently working on was about 52,000 words when I finished the first draft, and now it’s 70,000 words, and, I think, almost ready to share with my editor. Based on his notes and our conversations, it could grow perhaps another 10,000 words. A lot of revision, for me, is about discovering what essential core beliefs I have that my story is attempting to put into narrative. I never set out with a “theme” in mind; I just know I have a story to tell. Much later in the process, I discover a belief I have through the exploration of the book. This is the magic of writing—I learn something new about myself through this hard work.

Q: How do you market your work? Do you need an agent?

A: I am traditionally published, which means that an editor at a publishing house acquires my book and helps me make it into the best version of itself possible. The editor and publishing house are in charge of cover design, interior design, sales, publicity, and marketing, and a host of other things that I am still a little fuzzy about. Because I have chosen to go this route, I wanted to find an agent to help me connect with the right editors for my projects, and someone who can negotiate contracts. Not all writers want an agent, and finding an agent should not be something writers are trying to do when they are first creating the work. Art first, then craft, then business. For me, always in that order.

Q: When do you find yourself writing for professional reasons (blogs, emails, promotions)?

A: I teach in a wonderful low-residency MFA program. In that capacity, I do a lot of writing in the form of letters to my students about their work and comments throughout their work. I also answer interview questions and visit blogs as a guest, mostly when I have a new book to share. I write emails most days—to my editors, my agents, my writing friends. I interact with teachers and librarians who may want to bring me to visit their schools and libraries.

Q: What is the appropriate process for contacting editors and/or publishers?

A: The best way to approach an editor or publisher is through an agent who has agreed to represent your work—and remember, a real agent will never charge you any fees. Agents make a percentage (usually 15%) of the book’s advance and residuals. The best way to approach an agent is with a finished manuscript—a solid, clean story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, that fits the parameters of the category in which it fits (that is, one should know the basic expectations of, say, a picture book before submitting one). Make the book the best you can, and then enlist the help of a couple of readers you respect to get their input, and only submit your very best work. Research agents to find people who seem interested in representing the sort of work you are interested in writing. Follow the agents’ submission guidelines posted on their websites. Be professional. Be kind.

Q: Do you have any tips for young writers?

A: Listen to other people’s advice, but don’t forget to listen to your own voice, too. Be wary of changing a story so much to please others that you don’t recognize yourself in it anymore. If people point out problems with your work, thank them—don’t argue. Then go somewhere quiet and allow the criticism to sink in. That person has given you an opportunity. They may not be right about how to fix the problem, but they very well could be correct that there is a problem that needs addressing.

Be grateful; give more than you take—but don’t let people walk all over you, either. Often, people think that writers (especially women writers) should be grateful for the chance to write “for exposure.” Only do for free or for little pay that which you can do without resentment. It is okay to say no, in this and everything.

Q: Anything else I should know in regards to going into a writing based career?

A: Most writers supplement their income in variety of ways. I have seventeen books published and forthcoming—from Random House, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Lerner Press, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Harper Collins. In addition to writing, I teach, in Hamline’s MFA program, I travel to schools and libraries as a visiting speaker; I occasionally tutor high school students. There is no guarantee, even if your last book sold well, that your next book will sell at all. So, it’s imperative that writers are nimble.

I love writing. I love being a published author; it was a goal of mine since I was a young child. But the thing about achieving goals is that the heavens do not part and the gods do not bless your head when that goal is met. In order to lead a happy, fulfilling life, one must not rely on external successes or validations, because if you do, each success will leave you hungrier than the last. Find meaning in your work, but also in other areas of your life. And stay curious, always.

Image by Grace Lin

My 2015 title, Infandous, is a fairytale/mythology/Oedipus Rex contemporary surf and sculpture novel.

My 2017 title, What Girls Are Made Of, is about a high kill animal shelter, virginmartyrsaints, female orgasm, slavish desire, and the conditions under which we determine love.

Both books have been shelved as “Chick Lit.”

Perhaps this is a useful designation for some books, but as neither of these novels is lighthearted or amusing, and as neither of them is a romantic comedy by any measure, the category at the very least feels misleading.

What, I wondered each time the designation was conferred, could have brought the shelver to make this decision? It couldn’t be the flap copy, or the cover art, or the blurbs; none of these signifiers points in that direction. So, what was it?

I believe that the books have been labeled as “chick lit” because of a combination of two things: they are about teenage girls, and the author’s name is recognizably female. When a man writes about a teenage girl, it is never labeled as “chick lit.” When a woman writes from a male perspective, then, too, the book is called something else, regardless of how lighthearted and romantic the book might seem. So, what is it about the particular combination of books about girls, written by women, that makes them like a magnetic draw for the “chick lit” label? The answer isn’t complicated, and it makes me quiver with anger.

Even beyond the label “chick lit,” books by women written about the experience of being female are often seen as being books exclusively for female readers. I was thrilled when PopSugar called What Girls Are Made Of “a must read for women of all ages,” and pleased when VOYA said the book “describes all things ‘girl’ in the brutally honest way” book, even if it is not easy.”

But even when a book is written about a girl and by a woman, even when it explores menstruation and female orgasm and slavish devotion to a boy, that doesn’t mean that it is only for readers who identify as female.

Of course, I am grateful that my book is being read, and that it’s been critically well received. And, of course, I do want girls to read this book… but I want boys to read it, too.

At its core, what troubles me about the term “chick lit” is what troubles me about funneling books about girls and women only in the direction of girls and women: both this choice and the term “chick lit” are ways of saying that books about girls and women are only for girls and women, and that only girls and women could (or should) find such stories interesting and worthy of time and attention.

Parents, teachers, and librarians need to make certain that books about the female experience are offered to readers who aren’t female, as well as those who are. There’s a lot of talk about windows and mirrors in literature; I am humbled (and sometimes saddened) that girl readers see themselves reflected in my books, but I also want boys and men to read books that unapologetically center femaleness.

After all, centering femaleness in not something that needs an apology, or a justification, or an asterisk, or a special, catchy, rhyme-y genre designation.

I emailed one of the websites that had listed my books in their “chick lit” category. I told them the designation was wrong. How, they asked, would I prefer to see my books categorized? I’ll tell you, reader, that it took all my chutzpah to reply—“Literature.”

“We’ll shelve them with ‘Fiction,’” came the response.

I’ll take it.

Today something amazing happened. The longlist for the National Book Award in Young People’s Literature was announced, and WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF was included. You can see the whole list here. I am absolutely floored to see WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF in such luminous, brilliant company.

This book, this weird, uncomfortable little book, cost me so much to write. It was painful. It made me feel ashamed, and ugly, and afraid.

And this book exists because Carolrhoda Lab/Lerner Press and editor Alix Reed were willing to give a home to it. I want to acknowledge how grateful I am. There’s a lot of stuff in this book’s 200 pages that raises hackles. That disturbs. That may offend. Alix Reed didn’t flinch. She didn’t ask me to skirt the hard stuff, or ease up, or edit out the ickiest bits.

Thank you, Lerner Press. Thank you, Alix.

I have written four essays for the Nerdy Book Club. I thought I could archive them here, together.

Here is the first, entitled PONDS & BRAMBLES:

By the time I was eight years old, I’d moved half a dozen times. My parents bought and sold houses, fixing each up and flipping it for a profit, before deciding when I was six to move us from urban Long Beach, California to rural Atascadero, halfway up the California coast, and onto a two-acre parcel with a murky pond and a hillside resplendent in poison oak.

All kids are weird—all people are—but at the time, like most kids, I thought I was the weirdest. I wore heavy glasses, wished for curls with a desperate passion, and wanted—more than anything, even curls—a friend. A true, heart-deep, magical friend.

There was a girl in my second grade class. Her name was Nona. I don’t remember very much about Nona, and to be honest, probably none of it mattered—her likes and dislikes, her opinion about horses versus ponies, her favorite subject in school. All that mattered was that she was willing to be my friend.

From my vantage point now, I can see that Nona was lonely, too. We filled a need in each other’s lives. We announced our friendship by holding hands at recess, swinging the bridge made of our entwined skin and bones between us.

If you’ve read THE QUESTION OF MIRACLES, you already know how this friendship turned out. Nona and I did not name our daughters after each other. I wasn’t her maid of honor. We didn’t double date to Prom. Our friendship didn’t even survive the school year.

In middle school, after having moved several more times, I found myself surrounded by pairs. I was a single shoe. No one needs one shoe.

A few more moves and a few years later found me a freshman enrolling at yet another new school, this time three months before the academic year ended. It was there that I met Shayna, the first real best friend of my life. She got me, and she loved me, and, yes, she needed me as much as I needed her.

Many years later, after Prom, after marriage, after having a daughter (and naming her after a place rather than a person), I was living in Corvallis, Oregon (where THE QUESTION OF MIRACLES is set), and eating at American Dream Pizza when I got a phone call telling me that Shayna was dead.

My first question was, “But she’s okay, right? She’ll be okay?”

Dead was too much for my brain to understand in those first minutes. Even now, years later, I still find my fingers tracing her phone number on the keypad; I still hear her voice in my dreams.

If you’ve read THE QUESTION OF MIRACLES, you know that the main character, Iris Abernathy, has a dead best friend. Iris is in Corvallis, Oregon, and she wants desperately for Sarah to not be all the way dead. She, like I, would settle for scraps. Anything.

You may not believe this, but it is true: When I sat down to write THE QUESTION OF MIRACLES, I wasn’t thinking of Nona, or Shayna. When Claude the psychic tells her story of ruined friendship to Iris, I was as surprised as Iris to hear her tale—my own tale—about that first formative heartbreak. When Iris yearns for the return of her friend Sarah who is well and truly gone, it never crossed my mind that I was calling out, yet again, for Shayna to return to me.

Writing does not right past wrongs. Writing does not resurrect the dead. But, at its best, fiction dips ladle-like into the murky pond of memory, somersaults recklessly down the thorny, poisonous bramble of childhood, and emerges with something precious, and beautiful, and maybe, even, magical.

Here is the second, entitled ORIGINS:

Every story comes from somewhere. Maybe it’s from deep inside, a fear or a hope the author can hardly name. Maybe it’s a memory—the smell of magnolia flowers and summer sun, or the nose-twitchy pepper of a family barbeque.

With my last middle grade novel, THE QUESTION OF MIRACLES, I didn’t immediately recognize where the story came from. It wasn’t until I had some time and distance that I saw the parts of my life that seeped through and became the story of Iris Abernathy.

Not so with my forthcoming middle grade novel, FAR FROM FAIR.

Listen. Once there was a family. There was a mother and a father and a daughter and a son. There were pets and there was furniture and matching dishes and a stack of cloth napkins, neatly folded. There was a climbing tree.

It was a beautiful family, and they were happy. Well. Mostly happy.

In the evenings after work, the father disappeared into the garage to smoke cigars and worry. The mother arranged and rearranged the dishes and the napkins and the furniture and remembered, like a dream, a time before family, when she had planned to be a writer.

One day, the father came home. It was late, and his eyes were wide-white and wild. I got laid off today, he said.

Sometimes, when we turn a corner, we don’t recognize we’ve turned it until it’s far behind. We look back and we see, oh, there it is—that was the moment everything shifted.

But some corners, we see clearly. We make a choice that defines us, even if it scares us. This family did that. They sold the house, tree and all. They sold the furniture and the dishes and even the cloth napkins. They moved—parents, children, and pets—into an ugly brown RV. They hit the road.

The father stopped smoking. The mother began to write. First, a blog, called People Do Things. Then, later, novels. Not everything was made perfect. But it was made different.

You will not be surprised to hear that I am the mother in this story. Those blog posts were the first bits of writing that brought me to the rich world of writing for children that now defines so much of my day and myself.

Here is a picture of our family with our old RV, for my blog:

And here is the cover for my forthcoming middle grade novel, FAR FROM FAIR:

This is story of a girl, Odette Zyskowski, whose parents decide to sell everything and hit the road. They have their reasons—some that she understands, others that confound her—but the whole thing seems to Odette to be terribly unfair. And the farther they travel, the further they move from what Odette thinks is fair, from the way she thinks things should be.

This is a story I always knew I would write. The material is too rich not to be written. But though its origin is our family story, Odette’s path veers widely from the map I’d drawn for it…as the best road trips tend to do.

I once read that science fiction is always by necessity both about the future and about the time in which it is written. I think all fiction is like that. This story draws heavily on my past, but it’s about the present, too. As I wrote the first draft of FAR FROM FAIR, my father’s terminal illness worsened until we were forced to begin imagining a world without him in it. And though I intended to write an adventure road trip story, my present situation worried its way into the manuscript. Terminal illness of a loved one, Odette learns, is another thing to add to her growing list of Things That Aren’t Fair.

Some stories we choose, some choices we make, and others are thrust upon us. The road curves.

Here is the third, written to share the cover of A BOY CALLED BAT:

The first character I remember loving was a little girl with straight brown hair who lived on Klickitat Street. I loved that she was stubborn and imperfect. I loved the way she saw the world from the particular angle that only she, Ramona Quimby, occupied in her family, her school and her community. As I got older, I grew to see that I also loved how Cleary’s books about Ramona were simple and small and, at the same time, about big, universal, earth-shattering matters of importance: What do we do when we perceive injustice around us, as when Ramona felt that her teacher didn’t like her? How do we deal with big unfairnesses, as when Susan Kushner steals Ramona’s owl design? How do we help the people we love make better choices, and what are our limits in the choices other people make, like when Ramona hid her dad’s cigarettes?

By the time I met Bixby Alexander Tam, the boy called BAT, I was already the author of six novels—four YA, and two middle grade. I think I needed that much practice to become the writer I needed to be for A BOY CALLED BAT. Writing a chapter book, I think, is a process of distilling and clarifying rather than watering down or simplifying. Bat, like Ramona, has to deal with the big and the small, mashed up together: a tease-y big sister named Janie; a desperate desire to keep the baby skunk kit his veterinarian mother rescues; the way he sees the world from his particular angle— he’s a younger brother with divorced parents. He’s an autistic kid and an animal lover. He’s a boy who loves things to be a specific way almost as much as he loves vanilla yogurt.

I remember how it felt to disappear into my very first chapter books, to meet characters who sprang from black marks on a white page to become real. Not sort of real, not kind of real, but as real to me as I felt in my own skin.

I cringed when Ramona messed up. I grinned when she was clever. Beverly Clearly gave me words for the big emotions I was feeling, but didn’t yet have a clear way of communicating.

Kids are whole people, already, with a rich emotional landscape and full-grown fears and dreams. Writing books for emerging readers is a powerful and sacred honor. And the thought that kids might weave the boy called Bat into their imaginations and memories, the hope that they might carry him forward with them through their whole lives, as I have carried Ramona—well, come on. That is as much as any writer, of anything, could ever hope for.

And here is the latest, which the wonderful Donalyn Miller titled CREATURE COMFORTS AND A BOY CALLED BAT:

I was seven years old when my heart was broken for the first time, by a girl named Nona who didn’t want to be my friend anymore because I was “weird.” It was my cat Sabrina who absorbed my tears in her thick black pelt, who purred and licked and butted me with her head over and over again.

When we moved a third time in two years, Murray the hamster hung out with me, happily accepting the cheese puffs I offered.

At eleven, I got an astonishingly bad haircut—short in the back, really short, with long bangs, a haircut that might have looked good on a person with different hair but most definitely did not look good on me. It was my dog Charlie, a gentle black lab, who comforted me. He didn’t care about my hair, not one bit.

At my grandparents’ house, where I spent most weekends and chunks of each summer, Nana’s fat poodle, Diggy, napped next to me in squares of sunshine on carpet as I read stacks of books and nibbled on chocolates and grapes.

When I was sixteen and my parents divorced, I headed to the stable and saddled up Rainbow, my moody mare, who seemed to know that day not to bite, not to buck, but to run, fast and sure, as I clung to her, wishing her speed could truly take me away.

All my life, whenever there has been something to celebrate, someone to mourn, there has been an animal beside me. So when I became a mother, it was a natural thing for me to share this particular sort of relationship with my kids.

My son had a difficult time getting close to other children; he often misinterpreted their actions, and he didn’t always clarify his intentions, leading to conflicts, misunderstandings, and hurt feelings all around.

Enter Vegas, Max’s new ferret companion—a bit of an ankle biter, a wily and stinky tube of a pet. A pet can be a friend; it can also be a social lubricant, as effective for getting the party started among kids as a margarita machine is for adults.

Vegas lived a robust ten years, a good long life for a ferret, and he had adventures great and small—escaping through our dog door, being hunted deep in the night by my husband and me, armed with flashlights; moving away from California in an ugly old RV along with his dog pal Sherman and our family, house sold, stuff gone; a year in Oregon, where his white coat grew lustrous and thick; back to California; through the years of my boy’s childhood and into his adolescence.

There are no friends like our animal friends. They speak to us without words; they lick tears and bound joyfully and comfort us endlessly, endlessly.

My grandmother died on Friday. She was my favorite person, my ardent benefactress and steadfast force of love. She was, like me, an animal lover, becoming, in her mid-eighties, a vegetarian, in spite of her abiding love for deli meats. She adopted a cat—Yoahim—after my grandfather died, and for six years, she cheerfully endured the absolute worst behavior from that cat.

He was endlessly biting her. Each time I visited Nana (usually once a week, often more), she had a new bandage somewhere on her body: her forearm, her calf, her chest. She had the delicate skin of a very old person, and the bites would result in a slow purple leak of blood beneath the surface, blossoming and blooming bruises.

He’d lace himself between her legs as she walked, sometimes stopping just in front of her, laying down, endlessly in the way.

Death by Yoahim, we used to joke. That would be how she would go.

It wasn’t, though Yoahim was with her at the end, as we were, her grandchildren. The cat didn’t want to get too close in her last hours; he watched and waited in the doorway of her bedroom, his pupils dilated, his usually-busy tail very still.

All my life, animals have been a comfort to me. Now that my Nana is gone, I comfort Yoahim. I brought him home to our messy house, to my already-full menagerie. This morning I found him wrapped in my daughter’s arms, his head on her chest. She was sleeping; he was not. When I pushed open her door, he looked up at me, his expression inscrutable.

The comfort I find in my animals, the comfort my Nana found in Yoahim, the companionship Max found in Vegas, the healing Yoahim might be finding in this very moment in the arms of my daughter—that, I think, is where some of us meet and find our best and truest selves: in the care and keeping of an animal friend.

Today, at long last, is BAT Day!

In celebration, I want to share this essay about BAT.

Welcome to the world, Bixby Alexander Tam!